Seven Days

In Country

Thanks to the antics of Paris Hilton and Nicole Richie playing spoiled rich girls shoveling manure in the boonies, the phase “the simple life” is hard to utter with a straight face. Calais writer Ruth Porter’s novel The Simple Life intends the title ironically. But it’s still an antidote to the televised heiresses and all they represent.

In the novel’s opening chapter, Jeff and Isabel Rawlings, a Massachusetts couple up for their 25th Green Mountain College reunion, get stuck in spring mud on a remote country road. They’re rescued by a nearby farmer, aged but able Sonny Trumbley, who frees the car handily with his ox team and refuses payment for the favor. Jeff is eager to return to civilization, but Isabel is charmed by Sonny, his oxen and his run-down farm. She sees in them “a life of simple, basic things, the life she had always yearned to live herself…” Fast-forward a year: The couple’s marriage has dissolved, and empty nester Isabel returns to Vermont with a car full of belongings, determined to figure out how to live the “simple life.” This, or something like it, is the plot set-up of innumerable post-1960’s Vermont novels. But anyone who expects The Simple Life to be the story of a middle-aged woman’s conversion to bucolic simplicity will be surprised by its scope and tragic depth.

The “simple life” turns out to be more complicated than it looks, and we see just how complicated when Porter’s third-person narrator enters the minds of the people whose lives Isabel covets.

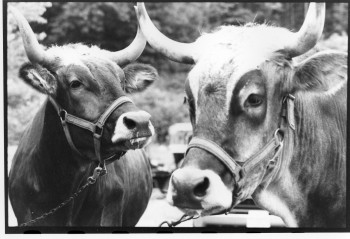

Sonny Trumbley wants to hang on to his ancestral farm, on its scenic piece of land. But he knows that when he dies, his live-in granddaughter Carol Ann will take the first chance to unload the unprofitable property. Soft-spoken and resigned, Sonny rests his hopes for the future on Carol Ann’s teenage daughter, Al, who accompanies him when he cuts wood and loves to drive his prize oxen, Buck and Ben. Both woodspeople at heart, Al and Sonny have an understanding that Carol Ann can’t penetrate. Yet she too is a sympathetic figure, who sometimes feels “as though she was the only grown-up” in the financially struggling family.

Porter even gives plausible shadings to a stock character of rural tales: the predatory real estate agent. Leroy Lafourniere is a flashy figure in the small town of Severance, with his big Lincoln, his string of mistresses, and his habit of gambling in Saratoga. He knows how to soften up a potential seller, and he has his eye on the Trumbley farm. But Leroy is also a deeply traditional man, at least in his own mind—“a country boy and local,” not “one of those downcountry types who barge in and start talking about business without even being polite first.”

It’s Leroy who seduces Isabel, distracting her from her plans to live like Thoreau. It’s also he who tells her, prophetically, “People come in here from some place else, and right away they want to change everything to make it just like the place they come from.” Ultimately, the out-of-stater becomes an almost peripheral figure in a tale about the downfall of precisely the sort of rural life she wants to preserve. The Simple Life is a rare book—a genuine “weepie” whose sadness feels earned, not schmaltzy or manipulative, because of the depth of detail Porter has used to make us feel part of the characters’ world.

Because The Simple Life is such a skillfully written and plotted novel, it’s initially a surprise to learn that it was self-published—not in the usual way, where the author works with a third party who prints copies on demand, but literally. Porter and her husband, veteran Vermont newspaperman Bill Porter, started their own company, Bar Nothing Books, to put out the novel.

Sixty-six-year-old Porter conceived The Simple Life 10 years ago and “finished it so many times,” she says. “Every time I finished it I’d send it out to publishers and get nowhere. By the time I finished it the last time, I knew I was going to do it myself.”

To become publishers, the Porters had to register with the secretary of state, join publishers’ organizations, figure out the mysteries of ISBNs and bar codes, and sign up for directories. They put up a total of $15,000 for the first thousand copies and $10,000 for the next 2000—an expensive strategy, but one Porter hopes will eventually break even. In six months, she’s already sold 1000 copies of the book, many of them through wholesaler Baker and Taylor, which sells hardbacks to libraries all over the country.

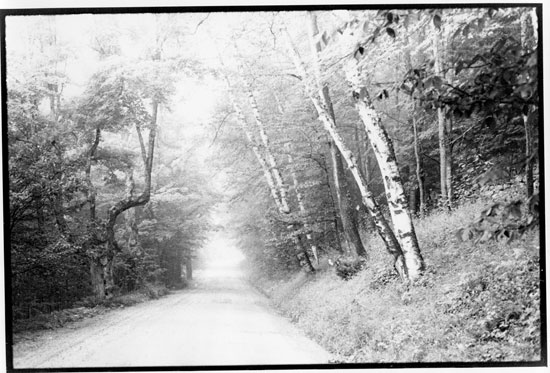

In return for her investment, Porter is able to say that “Every bit of (the book) is the way I meant it to be, even the commas.” Glenn Suokko, whom she hired to design the book, gave it a muted but elegant look; the Annex Press in Windsor printed it on sturdy paper. The cover image and the stark black-and-white photos that open each chapter are by Porter herself.

The Porters named their new venture after an older one. “We had a friend who used to come and visit our farm, and he would call it the Bar Nothing Ranch,” Porter says, chuckling. The name also refers to the company’s openness to publishing all sorts of books. Bar Nothing will publish Porter’s in-progress next novel, but she hopes other aspiring writers will “use the structure if they want to. They can buy ISBNs from us; we’ll tell them what to do,” she says.

Porter has one foot in the urban literary world and the other in the not-so-simple rural life she describes. Her grandfather was Maxwell Perkins, the celebrated editor of Fitzgerald, Wolfe and Hemingway. She was born in New York City into a family where “Everybody…thinks books are more important than anything else,” she says.

The Porters came to Vermont in 1963, almost on a whim. “We’d been married a couple of years, and we just wanted to get out of the city,” Porter explains. “We read this article that said South Dakota and Vermont were losing population and every other state in the United States was gaining population. So we said, “OK, let’s check out Vermont, and if we don’t like what we see in Vermont, we’re going to South Dakota.” They stayed.

Was Porter ever as naive as Isabel about the allure of the “simple life”? “Probably,” she says thoughtfully, suggesting that those days are far behind her. Soon after they arrived, the Porters bought the farm they still own and started figuring out how to make the most of the land. While her husband worked in town, Porter stayed on the farm raising four children and the food—and writing. “I pretty much made everything. I would spend the whole morning writing and then do the farm stuff in the afternoon and at night,” she recalls. “We used to buy like pioneers; we’d buy coffee and sugar and flour and salt, and that was just about it.” Since her children left home, Porter has “slacked off” some, but the couple still heats with their own wood and raises vegetables, beef and chickens.

It’s that kind of real-life experience that gives The Simple Life its richness. Porter adds a burnish of simple eloquence, as when she describes Sonny’s beloved oxen “walking heavily…rolling the way fat people do when their feet hurt.” The oxen, with their leisurely strength and their “rich smell of fruity fermentation,” are also drawn from life. Porter’s son kept an ox team, a project that originated when the family didn’t want to kill a newborn bull calf. Porter recalls how the teenager learned to manage the animals from old-timers—for instance, an “old guy who made doughnut hooks” showed him how to make a yoke by boiling the wood into a perfect curve.

Porter’s observation of the “old-time guys” who drive oxen was a major inspiration for the book. “If you ever go to one of those pulls, you see these guys, they have these wonderful relationships with (the oxen),” she says. “Especially the guys that work in the woods with them.” As she speaks, her intense blue eyes convey wonder at a complex and ingenious way of life that’s close to disappearing—without a trace of Paris-and Nicole-style condescension.

The Vermont Sunday Magazine

The Sunday Rutland Herald and the Sunday Times Argus

Simple but not-so-easy Vermont lives

This is a “November” book. In November the leaves have fallen, the grass has died, and snow has not yet sanitized the landscape. The world is a study in subtle hues of brown and gray. This is one of the few times of the year when you can see the rocks, bark and lichen – the earth in its natural state. In its own way it is quite beautiful.

The Simple Life by Ruth Porter is a book that nails the rural Vermont experience “dead nuts on” as character Sonny Trumbell might express it.

This is a Vermont that Vermont Life sweeps under the rug, because it ain’t pretty. This is the Vermont of doublewides, shadowy characters and human vulnerability that you can find on dirt roads everywhere, but never on the cover of a magazine.

Ruth Porter has the credentials for writing about the hardscrabble experience. Although raised in a small town in Ohio, she and her husband Bill operate a small farm in Adamant (doesn’t that sound like a name from a novel?) where they raised their four children, now grown and on their own.

“We grew all our own food,” she says. “We had cows, horse, chickens …” and, she adds, a team of oxen.

The oxen are central to the story of The Simple Life. Characters Isabel and Jeff are taking what they think is a shortcut to a 25th reunion at Green Mountain College when they encounter the scourge of Vermont spring: mud.

Soon their car is mired in ooze, as is their relationship. Along comes Sonny Trumbell, owner of a hillside farm, to liberate them. Rescue comes in the form of Buck and Ben, Sonny’s team of ox, who slowly and methodically extricate the couple’s blue Honda from the muck.

“He picked up his whip and walked to the front of his team. Holding whip high he said, “Come up,” softly. He walked backwards away from the oxen, and they walked slowly, steadily toward him while the car slid silently behind.

There was no straining, no drama, no loud noise, only soft, sucking sound of the mud and then the gritting of the oxen’s feet on the dry part of the road. When the car was out of the mud hole, the old man lowered his whip so that it hung in the air in front of the huge noses. ‘Whoa,’ he said in a deep, but quiet voice.'”

The experience affects the 40-something couple in polar opposite ways. Jeff wants to throw money at Sonny and get-the-hell-outta-here, while the sights, sounds and smells of the moment are indelibly imprinted on Isabel.

A year later the couple are divorced and Isabel has come to Severance (almost as good a name as Adamant), Vt., to start a new life. A stranger comes to town. … a development we’ve seen in many other stories.

The Simple Life was more than 10 years in the writing. Ruth Porter was never trained to write novels.

She holds no relevant degrees. She has never attended a writer’s workshop or been a member of a literary society. She has read a lot, mostly the classics. But she observes and listens very carefully.

The book is a labor of love. At one point, Ruth confesses, she read the book backwards, so that she could proof it without being distracted by the flow of the story. When the manuscript was finally finished, she considered the commercial publishing route, but it seemed more consistent with the traditions of hardscrabble farming to do it herself, following the models of Peter Miller, Burr Morse, Con Hogan, and other Vermont self-publishers. The package she has produced is highly professional, tightly written and pleasingly designed. The chapters are introduced by the author’s photographs that are, like her writing, solid and straightforward.

If you live in Vermont (outside of Chittenden County) you can’t help but recognize the characters. There’s Leroy LaFourniere, the realtor of French Canadian descent, who tilts between romantic and sleazy both in his business dealings and personal life. Roxy Fox is the landlady who has a heart of gold, but also a tendency to find herself on the wrong side of the tracks. Sonny lives on his hillside farm with his granddaughter Carol Ann, who is married to motorhead, Raymond. She works at the local diner; he relates better to engines than people. And then there is “Al,” short for Alison, the tomboyish 14-year-old daughter of Carol Ann and Raymond, who has a deep connection with her “Gramps” (Sonny) and his team of oxen. You know all these folks.

Isabel returns to Severance to start a new life and to fulfill a calling. She gets a room at Roxy’s, and a part-time job in Leroy’s real estate office. The stage is set for the story to unfurl.

The Simple Life is no light-hearted romp through the Green Mountains, but a deliberate and meticulously detailed story that moves stolidly forward at oxen pace. The lens through which the author views life in Vermont is not romantic, amusing or ironic.

The people are stooped and overweight, and they smoke. They have doomed affairs. They make poor decisions and pay the consequences.

The life depicted here may be simple, but it’s also stark and bleak, like November, leaving us on the precipice of winter. The Simple Life is a reminder to get your wood in early. What comes next is long, dark and cold.

The Montpelier Bridge

The Simple Life: Trouble in Paradise

Ultimately, the test of any book is the glue that holds it together—that’s narrative power.

What is narrative power? It’s the power of a good story —well told—to take you on a journey to another place. It’s the power of a story to seize on, capture, and hold fast a reader’s attention.

By any measure, Ruth Porter’s first novel with the disarmingly comforting title The Simple Life is a book with good glue.

Here is a novel —although the portents and scratch marks on the wall are there from the beginning —that seems so quiet, so rural, so peaceful, almost too quiet. Is there something sinister here? Porter’s story takes us step by step, with growing unease and gathering intensity, to a place that is violent and deadly.

In many ways, The Simple Life is about treachery and a loss of innocence. It’s also about a clash of values. And finally, because the story comes to stand for a way of life in Vermont that is not just threatened but has almost disappeared, as you put this book down, you hear a song that is tragic, sweet, and terribly sad.

As The Simple Life opens, Isabel and Jeff Rawlings, a down-country couple, have come back to Vermont for their 25th reunion at Green Mountain College. When their car gets stuck in the mud on a country road, Isabel and Jeff seek help from a local farmer. He comes along and pulls them out of the mud with his team of oxen.

To anyone who has lived in Vermont for a time, there is nothing too special about this scene; a couple of people from down country get stuck somewhere and a farmer pulls them out.

When Jeff offers to pay the farmer money for pulling his car out of the mud, the farmer gives no answer. Perhaps there is no answer to someone like Jeff from the city who can’t understand local values. In a country place, money is there. It has its uses. Time is there. It has its uses too. But there can be no answer to anyone who can’t understand the way one neighbor and another must cleave to each other in a rural place.

In her novel, Porter is writing about two worlds. In one world people are driven to pursue things with plans and projects and things to do. The marketplace energy that drives them forward causes them to worry about how they look, what other people think about them, the sort of car they drive, the $50 bills they can flash in their wallets, the deals they can cook up and score to their own advantage.

Porter takes us into another world. You hear the clank of a chain in the barn. You smell the animals, the sawdust, the hay, the manure. A gate or a door clicks open or shuts. It’s after supper and from outside the house, a patch of light hits the ground, and inside the dishes are being washed and people are talking.

It’s easy to feel there is a simple life, to feel that farming people rise with the sun, till the earth, cut firewood, observe the seasons along with Vermont’s white houses, grass and hillsides, the dark green forests and families at their chores.

These quiet pastoral scenes are not unlike what Isabel saw on that first night when she and Jeff got their car stuck in the mud and when she stood on the farmhouse porch. Porter tells us this is what Isabel saw.

The early light was as clear and pure as water. Beyond the black barnyard mud was a fence and then a wide field starting to turn green. In the center of the field was a huge, gray mound of rock, like a monument. On its far side was an old stone wall and beyond that a steep, wooded hillside. The trees were getting bright young leaves that shimmered with delight and foolish hope for the near year. She stood looking and looking, overflowing with the beauty of it.

The world that Isabel imagines “shimmered with delight and foolish hope for the next year.”

“Foolish hope,” indeed, which takes us to lines from Irish poet, William Butler Yeats.

We had fed the heart on fantasies

The hearts grown brutal from the fare

Surely, novelist Ruth Porter intentionally placed Isabel Rawlings at Sonny’s farm as the story comes to a climax. The purest relationship in the novel is the love and tenderness between Sonny, the old farmer, and his granddaughter, Al. And you have to feel when everything comes apart that Isabel is an agent. She’s in the picture trilling about her wish to lead a country life.

As the world of Sonny and Al comes crashing down, the message seems that the simple life is a fantasy. Fantasies aren’t real. Fantasies can’t last. What’s real is paying bills, paying taxes, heating an old house, getting old, facing death, whether it’s the death that’s awaiting you or that’s taken someone you love. What’s real is losing everything to predatory force.

In middle-age, Isabel Rawlings breaks out of the stifling, sterile cage that late 20th century America has built for her, and steps boldly into the oozing mud of her fantasy-driven new “simple life” in Severance, Vermont. She moves, over the course of a few months, from empty-nest mother and frustrated wife into a series of sticky relationships that include an affair with a small-time real estate hustler, a worshipful friendship with an old ox teamster, and a role as big sister to a lonely teenage farm girl who blossoms as they switch jobs with Alison playing teacher to Isabel’s eager pupil. Isabel plunges incautiously into her new life, working with no safety net and with too little experience into an unsheltered world where she is a stranger in a strange place. The lack of security makes every day an adventure, marked by soaring highs and soul-sinking lows. But the fantasy life Isabel leads is just plain life to everyone else, and the dream that brings her to Vermont starts to crumble even before she realizes she’s living a fiction. She discovers that life is never simple.

Chapter One

“I really can’t believe you thought there was something going on between Susan Brownmiller and me.”

“Well, I wasn’t the only one.”

“Honestly, Is, you just make things up. You only see what you want to see. I haven’t even said two words to her for twenty-five years. You just make up this whole thing, and then you believe it.”

Isabel hunched a little lower on the seat. She looked through the windshield, but she didn’t really see. That was the convenient part about driving around while they had a fight. At least they didn’t have to look at each other when they hurt each other.

“It’s not the first time,” she said, but she didn’t say it very loud. She felt too miserable to make an effort.

“What did you say? I couldn’t hear that.”

He looked around at her then, as much pain on his face as she could feel on her own, and she was suddenly sorry. “I said I knew it was a dumb idea to come to the reunion.”

That was when the car bogged down and stopped. Jeff stepped on the gas, and the engine whined, but they didn’t move.

“God damn it! Now look what you made me do. I should have been watching this stupid cow path. Why in hell can’t they pave the roads in Vermont? They’re too stingy, that’s why.” He squeezed the steering wheel until his knuckles were white. He even tried to shake it.

Isabel looked away in embarrassment. Beyond the muddy road, set back from it, was a white farmhouse. Not particularly beautiful or particularly neat, it sat at the center of its own universe with its barn beside it, in a circle of fields, ringed by wooded hills, ringed by blue, more-distant hills. There were no people around, but Isabel could see that the ones who lived there lived in peace and harmony with nature, a life of simple, basic things, the kind of life she had always yearned to live herself, only she didn’t know how.

The only sound was made by the spring peepers, still occasional because it was still daylight, although night wasn’t far off. The light was transparent with that purity that comes in the early evening in early spring.

She looked around at Jeff and smiled and said, “I guess that’s why Vermonters always talk about mud season. I remember now.” Too late she realized that she had forgotten all about their fight, assuming, without even thinking of Jeff, that he was seeing what she was seeing.

“It’s just like you to laugh. How could you think it was funny? We can’t even get out of the car. There’s mud everywhere. You probably haven’t noticed—you’re so damn unrealistic.”

She could feel him trying to reel her back into the fight, but it was as though she was suddenly on the other side of the window, out there with the peaceful farmhouse. Watching Jeff from that distance, it was different. It didn’t matter.

“Let’s get out and look around.”

“We can’t! There’s no way to know how deep it is. It’s horrible.”

“It’s only mud.”

“You never care what a mess you are anyway.”

She felt the sting of that. “I’m as dressed up as you are. Look at my shoes. They’re much more delicate than yours. And I have stockings on, and a new dress. I’m just braver, that’s all.”

“It’s not your class reunion, so you don’t care.”

“I’m going to push us out, and then we can go back to the motel, and I’ll clean up.” She didn’t even look at him or wait to hear what he had to say. She opened the door with determination.

She didn’t want him to see any hesitation, so holding her breath, as though that would keep a little more of her out of it, she poked the toe of her shoe at the satiny, brown surface of the mud. Her shoes were new, high heels of wine-colored suede. She had looked down at them often and with pleasure while Jeff was talking to his classmates. It was hard to see that delicate and stylish foot disappear. The mud clutched coldly at her ankle, and she still wasn’t touching bottom. She gasped.

Jeff was leaning over the steering wheel so he could see. “Now you know what I mean.” His smile was bitter.

“It surprised me, that’s all. I’m still going to push us out. Just wait.” She put the other foot in and slid off the seat until she was standing, gasping a little and trying to hold up the skirt of her new dress with the mud halfway up her shins. “Wow. It’s cold.”

She started walking toward the back of the car. She moved in slow motion, pointing her toes because the mud was trying to take off her shoes. She wished she had thought of taking them off herself. If one got lost at the bottom of the mud hole, she’d never find it again. When she got to the back of the car, she had to let go of her skirts, which were long and full. The bottom of her dress slid slowly out of sight into the mud.

The car was Jeff’s, a dark blue Honda that was small and light. One good push would do it, the way it did sometimes when the snow was deep.

“I’m ready whenever you are.” She waved at the back of his head through the rear window.

He raced the engine, and she reached down to get a good grip on the bumper, prepared to give it everything she could all at once. She could feel the jerk when he put it in gear, and she could hear the engine revving. Mud sprayed everywhere, but that was all. Maybe she hadn’t started to push at the right time.

“Try it again.” But even as she called, she knew nothing would happen. And nothing did.

Jeff turned the engine off and stuck his head out the window. “It’s no use, Isabel. I told you so. I’m going to get out. Maybe the people in that house will let me use their phone.”

“I’ll do it. You can stay there.”

“Don’t be ridiculous. Look at you. They’d never let you inside.”

“By the time you get out, you’ll be just as bad.”

“No I won’t. You watch.”

When Isabel looked through the back window, she could see Jeff climbing laboriously into the passenger seat. He was so long-legged, and his car was so small, that it wasn’t an easy maneuver. She walked in slow motion around the side of the car, although she didn’t want him to think she had come to see him fall in the mud. She held out her hand to help him, but he jumped past her, turning his body slightly, refusing her help. She looked down at her outstretched hand and saw that it too was covered with mud. She wiped both hands on her skirt and followed him across the front yard to the farmhouse feeling secretly disappointed. He was right about that much anyway. He had jumped almost over the mud, so that nothing got dirty except his shoes. Isabel looked down at her dress. The whole thing was spashed with mud, and there was a heavy band of it around the bottom.

Jeff went up onto the porch and rapped smartly. The glass in the door made a loose, rattling sound. “They ought to do something about that before next winter,” he said.

Isabel stayed at the bottom of the steps. In his dark suit, tall and thin and precise in front of that old-fashioned door, he could have been a salesman. With his neat tortoiseshell glasses he looked as though he would be selling something intellectual. He knocked again and then paused, listening. When he didn’t hear anything, he cupped his hands around the sides of his eyes and looked in.

“What do you see? Tell me.”

He turned to look at her, blinking in the light. “I don’t think anyone’s in there.”

“What’s the room like then?”

“I don’t know, just sort of dark. I think it’s a hall. I saw some stairs.”

“Why don’t we try the back door? Maybe they’re in the kitchen and can’t hear you.”

“Maybe.”

Isabel went first along the path through tall bushes which were just getting their new leaves. She was sure the kitchen door would be on the same side of the house as the big barn, but she didn’t say it out loud. Jeff hated it when she was so positive about things she couldn’t possibly know. When she got to the small back porch, she stood aside to let him be the one to do it.

The back door was half open. Jeff pushed it a little farther and stuck his head inside and said, “Anybody home?” He tilted his head, waiting for an answer, but there wasn’t one.

Isabel said, “I guess nobody’s in there. That’s too bad.”

“I don’t see a telephone, but I could go in and look for one. What do you think?”

“Maybe they’re in the barn, doing chores or something.”

“We could look.”

“I wonder what kind of people live here.”

“All I want to know about them is whether they have a telephone or not.”

He came down the porch steps and crossed the driveway to the barn. Isabel followed trying not to feel annoyed. Their fight seemed to be over, and she didn’t want it to flare up again.

They went through a door that creaked, into a dusty, low room with old work clothes and bits of harness hanging on nails around the walls. A bare bulb hung from the ceiling in the center of the room. It was lit, but it gave off a dim light through the thick lattice of cobwebs around it. It was much warmer now they were out of the wind.

Jeff crossed the room and went through a low doorway on the far side. When she saw him ducking under the large beam that went over the door, Isabel thought of Alice in Wonderland. She stopped to laugh and then had to hurry to catch up. On the other side of the door was a dark passage, spidery and empty. She felt an irrational stab of fear that lasted until she almost walked into him around the bend of the passage.

The hallway was suddenly wider and higher with light coming in through big open barn doors at the end. It smelled of fresh sawdust and animals, a smell of the circus. There was a radio playing faintly somewhere, but no people. They walked down the hall looking into the empty animal stalls on each side.

“I wonder how far it is to the next house. I can’t remember seeing any houses before we got stuck. Can you?”

“I guess I wasn’t looking. There must be somebody around here though, or they would have turned off the radio.”

“Maybe they leave it on all the time to fool people. Damn this god-forsaken place!”

Isabel walked to the open doorway and stood there looking out. The early evening light was as clear and pure as water. Beyond the black barnyard mud was a fence and then a wide field just starting to turn green. In the center of the field was a huge, gray mound of rock, like a monument. On its far side was an old stone wall and beyond that a steep, wooded hillside. The trees were getting bright young leaves that shimmered with delight and foolish hope for the new year. She stood there looking and looking, overflowing with the beauty of it.

“Come on, Is. What are you standing there for? We’ve got to do something.”

“It’s so beautiful. I was just looking.”

“We don’t have time for that now. It’s almost six o’clock. We’re going to miss the dinner for sure, and we paid for it too.”

By the time Isabel turned around to follow him, he was already near the bend in the hallway.

“It’s going to be dark before we can get a tow-truck out here. I bet they’ll have to come all the way out from Severance. I’m going to go into their house and use their phone. Let them sue me.”

Isabel had gone a few steps before she turned back for one more look. Something moving had caught her eye just as she turned away. Coming out of the woods toward the gap in the stone wall were two people looking very small compared to the two huge, tan cows that walked behind them. She had to blink to make sure she was really seeing what she thought she saw. Framed by the dark doorway, the bright field with the tiny figures was like an N. C. Wyeth illustration for a book she had read long ago. Now she could even hear a ghostly jingling of chains.

“Jeff, come back. Here they are.”

“What?” He stuck his head around the corner. He looked exasperated.

“The people. Come and see. These must be the people who live here.”

He said, “Where? I don’t see anybody.” But he came back and stood beside her in the doorway.

“Isn’t it beautiful? That’s a team of oxen, isn’t it? You don’t often get a chance to see something like this. An old man and a boy. The boy’s the one holding the stick. Do you think he’s telling the oxen what to do?”

“I don’t know, and I don’t care, but I tell you, I wouldn’t walk right in front of them like that. They’re not even looking back to see how close those cows are getting.”

“They’re trained to do that.”

“Well, I wouldn’t walk in front of them, no matter what. You couldn’t be sure. You never can tell about animals, even dogs. It’s always a mistake to trust them.”

“Don’t you feel as though this is a magic place, Jeff? Like maybe we fell into a fairy tale?”

“What—the wicked witch of the mudhole who snatched our car?”

“I don’t mean that. It’s just so beautiful here, and strange. I mean it’s so different from home and the bookstore, even from the reunion….”

“I agree with you about that. It sure is different. I’ll be glad to get back to where things are normal.”

“No, I mean, it’s so beautiful that it seems enchanted, like in a story. That’s what’s different about it. I mean it’s not really surprising that we could look out there and see those people with oxen. Don’t you feel that way too?”

“No.”

“Not even a little?”

“Not even a little. It’s very scenic. Sure. But I want to get back to the reunion where I can be comfortable.”

“Oh, I wish…”

“What?” He sighed. “You’re never satisfied with the way things are, that’s your trouble.”

“Well, I’m not the one that minded about the car getting stuck. I’m even glad it happened.”

“Oh for God’s sakes. The things you say. It’s because you don’t think. You’ll probably be sorry before we get out of this mess, even if you don’t know it now.”

“I bet I’m not.”

“We’ll see.”

“Jeff, this is serious. Please listen.”

“What is it now?”

“When we sell the bookstore, we’re going to move out of Abingdon, aren’t we?”

“Probably.”

“I mean, I know we’ve talked about it a lot, about where we’d go .”

“There isn’t any hurry. We’ll probably go from place to place for a while. Until we see….Florida, Palm Springs, Arizona. We can try them all.”

“I have a much better idea.”

“What’s that? Look, they’re getting close. God, are they big! I bet they’re dangerous. Look at those horns!”

“Let’s take the money and buy a farm like this one, around here some place.”

He looked around at her. “You have got to be crazy.”

She met his look of amazement. She could feel her jaw getting tight. “No I’m not. I’m completely serious.”

“Well, it’s a crazy idea then. Here, look out! We need to get out of this doorway.” He grabbed her by the upper arm and pulled her into an empty stall.

The clanking of chains was much louder, and suddenly the light coming through the large doorway was blocked, and the huge team rolled into the passage filling it completely. The old man walked nonchalantly right in front. He held the whip up before the noses of the oxen and said, “Whoa.” His voice was surprisingly deep for such a gnomelike person.

Isabel stood beside Jeff in the doorway of the empty stall. The gigantic, horned heads were right on the other side of the opening. Isabel had never been that close to really large animals before. The smell of them, a rich smell of fruity fermentation, filled the air. They turned their heads slowly and in perfect time with each other, and four enormous brown eyeballs rolled slowly around to look at Isabel with stately and detached curiosity. She felt small and very vulnerable standing there, wondering if they were going to object to her red dress. Did oxen hate red the way bulls were supposed to? Maybe they only minded bright red, not the dark wine-red she was wearing.

The old man was standing in front of them, unfastening something on their yoke. When the oxen turned to look at Jeff and Isabel, the old man looked in their direction also. His gaze was as calm and unsurprised and slow as that of his cattle.

Jeff cleared his throat nervously and said, “Hello. My name is Jeffrey Rawlings. I was wondering if I would be permitted to use your telephone.”

The old man nodded and turned back to the yoke without speaking. He had to stand on tiptoe to reach the top of it.

Jeff turned to Isabel and gave an exaggerated clownlike shrug, as though he wanted to say, “OK, so what do I do now?” There was no way he could leave the stall.

The huge beasts were chewing in unison, with great sideways, rolling, jaw motions. Isabel could hear their teeth grating against each other. She felt herself slowed to their time. She let her eyes roll around the way theirs did to see who was going to make a move next.

Jeff shifted from foot to foot and then said, “Our car is stuck in your mudhole. I believe we need a wrecker.”

The old man’s eyes flicked across Jeff’s face and then back to the yoke. He reached in his pocket and took out a big metal pin, put it through a hole in one of the bows and hit it with the heel of his hand to drive it into place. Without looking up from what he was doing, he said, “I’ll come take a look.”

Jeff looked surprised. He opened his mouth and took a breath, as though he was about to speak. Then he closed his mouth again without saying anything. He flapped his arms at his sides several times, but there was nothing he could do either.

The old man picked up the whip which he had propped on the floor in the doorway. He made a flourish in the air with it, and said, “Come up,” one soft gulp of a word. Then he turned and marched down the hall with the whip resting on his shoulder like a rifle. With heavy dignity, with a ponderous swaying of bodies and clanking of chains, the oxen moved forward after him.

Jeff and Isabel peeked out the door to watch. Isabel whispered, “But they’re going the wrong direction.” Jeff frowned and shook his head to shut her up.

The old man stood at the end of the passage, pointing with his whip to the stall on his right. The oxen walked heavily toward him, rolling the way fat people do when their feet hurt. When they got near, the old man said, “Haw,” and the oxen disappeared into the empty stall. Isabel could hear them shuffling, clanking, and creaking as they moved around in there while the old man stayed where he was at the end of the hall. After a minute their heads appeared in the doorway again. The old man was pointing down the hall with his whip. They turned out into the hall and down it. Isabel and Jeff had to step back as the oxen swept past filling the hall with their bodies. They blocked the light again as they went out of the barn in a rich cloud of animal scent. The old man walked out behind them.

Isabel and Jeff looked at each other. The barn seemed much emptier than it had before the oxen came in.

“What’s next?” Jeff said.

“I think they’re going to look at our car.”

“Well, I hope he doesn’t think I’d let him touch my car with those things.”

“Jeff, they’re amazing. Didn’t you think it was great the way he turned them around?”

“Cause I’m not, and that’s all there is to it. I’m going to call a wrecker.”

“They looked plenty strong enough.”

“That’s just what I’m afraid of. There’s no telling what they would do to my poor car.”

Isabel started out the back door after the oxen. She didn’t want to miss any of it. The barnyard mud was soft and black, and every place the oxen had stepped was a round hole filling with water. She hesitated. The light-colored mud on her feet was already caked and dry.

Jeff called to her from the other end of the passage. “Come this way, Is. You don’t want to walk through that muck. We can get back to the car this way.”

Isabel followed him back through the barn the way they had come in. When she stepped outside, the air was clean and sharp and smelled of ice. It was colder, and the spring peepers sounded louder than they had when she stood at the other end of the barn. The sky was still luminous, but the first stars were beginning to prick through. The dark, peaceful hills made a safe circle around the fields and buildings. Isabel felt like bursting from the beauty of it all.

Down the road, the oxen were just getting to the car. The old man was right beside them, and Jeff was trying to catch up. His arms were swinging and his suit jacket flapping with the awkward, scarecrow way he had of walking when he was in a hurry. Isabel followed slowly, trying to take in everything beautiful around her, refusing to be drawn into Jeff’s anxiety. The lights were on in the kitchen, and the door was shut. That was where the boy had gone.

By the time she caught up to them, the old man and Jeff were standing side by side where the deep mud ended, looking at Jeff’s car. The oxen stood back a few feet, facing the car and chewing thoughtfully.

“It looks pretty helpless, doesn’t it?” she said, as she stopped beside Jeff. “Like a wounded animal caught in a tar pit with its door open like that.”

The old man gave no sign that he noticed her arrival, and Jeff looked at her as though he had never seen her before. He turned to the old man.

“You really don’t think I need to call a wrecker?”

“You do whatever you want.” He picked up his feed store cap by the bill and resettled it on his head. “It’s your car that’s stuck.”

“You really think you can pull it out by yourself?”

“With my team.”

“I don’t know what to do. It would save a lot of time and money.” He ran his hand through his hair. “But they could hurt it, and it’s only two years old. It doesn’t even have any serious scratches on it yet.”

He looked over at the old man, but the old man stood there tapping the toe of his workboot with the end of his whip, as though he hadn’t heard a word.

Jeff looked around at Isabel. “What do you think we ought to do?”

“What can happen? There’s nothing for the car to bump into. I don’t see what we’re waiting for.”

She caught a quick glance of appreciation from the old man.

Jeff said, “Well, OK, but remember, Isabel, this is your idea. I just hope we’re not making a big mistake here.”

The old man had moved in front of his oxen and raised his whip, but he hadn’t started them moving. He was looking at Jeff, waiting for the word to go.

Jeff nodded to him. “Yes,” he said. “My wife says to do it.”

The old man said, “Gee-up,” softly, and walked his team in a wide circle so that when he halted them, they were standing in front of the car with their backs to it. He ducked under the yoke, took down the chain that was draped over it, and laid it out on the ground between them with one end hitched to the large iron ring that hung from the center of the yoke. Then he peeked out over the back of the ox that was nearest to Jeff. He was so short and the ox so tall that the only parts of him that showed over the ox’s back were his eyes and the top of his head in the faded red cap. “You might want to steer your car,” he said to Jeff, and then he disappeared, not waiting to see what Jeff was going to do.

Jeff didn’t move. Isabel said, “Do you want me to do it?” She was excited.

Jeff looked down at her legs and the bottom of her skirt where the mud was flaking off in dried chunks. “No thanks,” he said sourly. “I’ll do it myself.” He went to the edge of the mudhole and gave a great flapping jump into the open door of the car. He closed the door and climbed into the driver’s seat. Isabel watched him trying to maneuver his long legs in the narrow space.

When she looked at the old man again, he was crouched under the front end of the car trying to find a place to attach the chain. He seemed indifferent to the mud. In a minute he stood up and walked stiffly around to where Jeff was sitting by the open car window.

“Take it out of gear, but don’t turn on your engine. Just keep your wheels straight.”

He picked up his whip and walked to the front of his team. Holding his whip high, he said, “Come up,” softly. He walked backwards away from the oxen, and they walked slowly, steadily toward him while the car slid silently behind. There was no straining, no drama, no loud noise, only the soft sucking of the mud and then the gritting of the oxen’s feet on the dry part of the road. When the car was out of the mudhole, the old man lowered his whip so that it hung in the air in front of the huge noses. “Whoa,” he said in a deep, but quiet voice.

Isabel spun around and around in the road, saying, “Hooray, hooray,” until her muddy skirts were flying out in a circle around her. When she stopped, she almost fell over with dizziness, but the others didn’t notice. The old man had already unhitched the chain from the car, and Jeff was walking toward him with his hand outstretched and a big smile on his face.

“Thank you very much Mr….uh….”

The old man looked at Jeff’s hand coming toward him. Then he looked down at his own hand. He wiped it up and down on his trouser leg, looked at it again and gave it to Jeff to shake.

“Thank you. What do I owe you?”

“It wasn’t nothin. I didn’t even have to yoke ’em up.” He walked over to his team, and Jeff followed. Isabel joined them.

“But don’t you want some money?”

The old man watched the toe of his boot kicking at a little ball of mud on the road. He said nothing.

“I would have had to pay the wrecker.”

The old man didn’t seem to feel any responsibility for the awkward pause.

Finally Isabel said, “It’s amazing how strong they are. I wouldn’t have believed it. I don’t think I ever saw any oxen up close before.”

The old man smiled and grabbed the horn of the ox nearest to him. He jiggled the huge head back and forth affectionately. “Yup. They’re good boys, all right. They know their job.”

“Do they have names? I mean, what are their names?”

He smiled at the huge head he was holding on to. “This here is Buck. He’s my nigh ox. That’n over there is Ben. He’s the easy-goin one. He just takes life as it comes. Buck ‘n Ben, that’s them.” He jiggled Buck’s head, making him nod in agreement. Then he turned to Isabel. “Where are you folks from?”

Isabel was just opening her mouth to say Massachusetts when Jeff said, “We went to Green Mountain College. I’m up here for my twenty-fifth reunion. Boy, time sure flies. I guess I’m getting old.” He chuckled a little.

Isabel didn’t smile, and neither did the old man. She said, “You live in a beautiful place.”

“It’ll do.” His voice was gruff, but he tilted his head toward her in gentle acknowledgment. She felt they understood each other, although she couldn’t have said why. They were all three silent, looking at the ground. Then Jeff cleared his throat.

“Well, thank you very much, Mr…..I’m sorry I didn’t catch your name.”

“Trumbley. Sonny Trumbley.”

“Well, thank you so much, Mr. Trumbley. If you’re sure you won’t take anything for it. Come on, Isabel. We’d better get back to GMC before they send out a search party.”

Sonny Trumbley spoke to his oxen, and they all three started toward their barn, walking companionably side by side. Jeff got as far as the door of his car, and then he stopped.

“Mr. Trumbley,” he called, “Oh hey, Mr. Trumbley. Could you wait a minute?”

The old man stopped and turned to look back. The oxen continued on their ponderous way.

“I have to go back the way I came. Could you just wait until I get across this place again? In case I get stuck.”

The old man shouted to his oxen to whoa, and they all three stood where they were, waiting without interest while Jeff and Isabel got into the car, and Jeff turned the car around and drove it back through the mud, making the engine rev much too much in his nervousness.

When the car was safely across, Jeff honked the horn, and kept on going. Isabel looked back. She just had time to see the three of them walking off side by side again before the car went around a bend in the road.

It had gotten much colder since the sun went down, and Isabel had left her coat at the motel. Now that she was in the car, she realized how cold she was. She turned the heater up as high as it would go.

Neither one of them spoke for a few minutes, and then Jeff said, “It’s twenty of seven. You know we might even have made it to the dinner after all, except that we’re going to have to go back to the motel so you can change.”

“Oh.” She thought for a minute. “Do you want me to go like this?”

He looked around at her, as though trying to see if she was serious, but he didn’t ask.

“I could probably knock off the worst of the mud. And most of me will be under the table. I mean, if you want me to.”

“Isabel. Don’t be ridiculous. It would be too embarrassing. We’ll have to miss it.”

“Well, OK. It’s up to you.” Now that they had left that magic spot, she could feel the disagreeableness settling over her again.

“You don’t ever care about anything, do you, Is?”

“Maybe I’m just different than you.”

“Hah!”

“That was a great place, wasn’t it? And an amazing old guy.”

“I would have rather gone to the dinner.”

“Did you see? He had on suspenders and a belt.”

“I wasn’t really looking at his clothes.”

“Well, he did. I wonder why.”

“He probably didn’t want his pants to fall down. Who cares?”

“You know, Jeff, I’m serious about this subject. You don’t pay any attention to me when I try to talk to you about it, but….”

“How an old man holds his pants up?”

“No. You know that’s not what I mean. I’m serious about what we do when we sell the bookstore.”

“Let’s wait and see how much money we get for it. That old guy you liked so much would probably say, ‘Don’t count your chickens before they hatch,’ or something.”

“That’s OK, but what I mean is this—I think you and I have kind of different ideas about what we’re going to do with that money, and I think we ought to talk about it. I mean, I think you think I’m going to go along with what you want to do, and I might not.”

“Just what do you mean by that?”

<“There. I’ve said it, and I’m not sorry. You always think I don’t know what goes on in the real world, and I always have my face in a book, and I don’t know how to take care of myself, and I suppose it’s all true. But there’s another part of it that you haven’t got right. That’s going to be my money too, and I have some ideas about what I want to do with it, and even if they are dumb ideas, I have a right to try them out.”

“Not if it’s going to waste the money, you don’t.”

“Look, I don’t want to start the fight up again, I just mean we have to talk about some stuff. I’ve been looking around at the reunion. When you were talking to your friends, there were some times when I didn’t have anybody to talk to. And I’ve been wondering why we got married in the first place. I can’t remember any more.”

“Because we loved each other.”

“Yeah, but I’m not sure what that means—what we meant by that.”

“Well, it just….”

“And more important, I’m not sure what that has to do with now.”

They were looking straight ahead again, both of them being careful not to see what effect their words were having on each other.

“Well, at least we made it back to the paved road. I guess we don’t need to talk about this any more. Let’s go to the motel, so you can clean up, and then we can go into Severance for some dinner. OK? We can be back in time for the party.”

“Sure. Fine. But we’re going to have to figure this out some time. It’s not that being at that farm tonight changed my ideas about what I want to do with my life….”

“Isabel, you sound like a child. You’re forty-four years old. Remember?”

“I know. But I feel like I haven’t done anything yet. I don’t feel old.”

“That’s why I want to get out of the bookstore now, while we’re still young enough to enjoy ourselves.”

“I don’t want to just have fun. There is something I want, something I need to do, and being at that farm made me think it wasn’t just a dumb idea.”

“Those things always sound better in books than they do in real life. That’s your trouble—you read too much. Look at Thoreau. He talked a good game, about how cheap it was to build his cabin, for instance. But the truth was that he didn’t know anything about building. There were bent nails that he wasted lying all around that cabin. And nails were expensive in those days.”

“I know, Jeff. You’ve told me that a million times, and I always used to believe you, but not any more.”

“I don’t know what you could possibly mean by that. It’s a fact, for God’s sakes. Sometimes I don’t understand you at all, Isabel.”

“It doesn’t make any difference. That old man we saw tonight doesn’t care about stuff like how many nails Thoreau used up. He’s living his life simply, the way he always has. I don’t see why I can’t live like that too.”

“Oh for God’s sakes, you’re the simple one. I just wonder if that old geezer was up to anything. There’s something funny about the way he wouldn’t take any money.”

Isabel couldn’t think of anything to say to that. She shivered and hunched a little lower on the seat, but she felt a new determination, and she resolved not to forget it.

“He never would look me in the eye either. I hope we’ve seen the last of him.”

“Well, I haven’t,” Isabel said, but she didn’t say it out loud. It could wait.

I took all the photographs in this book, including the one of myself. I took the pictures of the oxen at an ox pull in Grafton, Vermont. They belonged to Ernie Woods of New Hampshire. Their names were Jake and Sam, and I knew they were Sonny’s ox team the moment I saw them. I had always pictured his oxen as Brown Swiss, but these guys were Brown Swiss, Charolais, Holstein, and Chianina. I think it’s their complicated heritage that makes their faces so interesting.