An interview by Ann Hagman Cardinal which first appeared on March 9, 2010, on the site, www.blogcritics.org

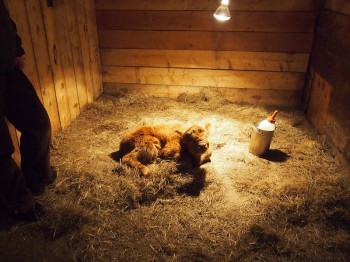

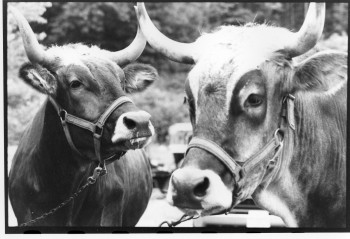

When you hear of a writer who has a literary pedigree like Ruth King Porter — the granddaughter of Maxwell Perkins, editor to Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald and Thomas Wolfe — certain images come to mind. Oak-lined studies and writing garrets, or maybe cocktail parties and New York hobnobbing. Instead, Ruth Porter spends her day tending her beef cows, caring for her horses and harvesting vegetables. And somewhere in there she sits at her kitchen table and works on her novels in a not very glamorous, but in a comfy and cozy Vermont kind of way.

Ruth was born in New York City, but moved to Ohio when she was quite young. In 1964, she and her husband, journalist Bill Porter, moved to Vermont. She couldn’t even make coffee when she got married, so she learned what she could about cooking and farming from books (she cites Little House in the Big Woods as an excellent source for information, particularly about churning butter and curing meat). They raised four children — not to mention dozens of sheep, pigs, cows, horses and chickens. Though she grew up knowing of her famous grandfather — oft described as the most famous literary editor — she didn’t know him and was quite young when he died. Ruth wouldn’t start writing until after she began to raise a family. Once she got a taste of the struggles of the publishing world while shopping her first novel, The Simple Life, she found she shared her grandfather’s rebellious spirit (he had to fight to publish Fitzgerald and Hemingway) and decided to go rogue and begin her own publishing company, appropriately named Bar Nothing Books.

Ruth was born in New York City, but moved to Ohio when she was quite young. In 1964, she and her husband, journalist Bill Porter, moved to Vermont. She couldn’t even make coffee when she got married, so she learned what she could about cooking and farming from books (she cites Little House in the Big Woods as an excellent source for information, particularly about churning butter and curing meat). They raised four children — not to mention dozens of sheep, pigs, cows, horses and chickens. Though she grew up knowing of her famous grandfather — oft described as the most famous literary editor — she didn’t know him and was quite young when he died. Ruth wouldn’t start writing until after she began to raise a family. Once she got a taste of the struggles of the publishing world while shopping her first novel, The Simple Life, she found she shared her grandfather’s rebellious spirit (he had to fight to publish Fitzgerald and Hemingway) and decided to go rogue and begin her own publishing company, appropriately named Bar Nothing Books.

Ruth’s latest novel — released this month — is titled Ordinary Magic. The storyline focuses on the Willards, a traditional Vermont farming family whose tale is told in straightforward but elegant prose that mirrors the personalities of the characters and the culture in which they live. The alternating points of view and voices provide pieces of an intricate puzzle that come together to create an understated but enchanting image of life in rural Vermont.

How do you manage to fit the writing of novels into farming life?

I’ve always done the writing first. I would get the kids off to school and do the chores that had to be done, and then I would take the rest of the morning for my writing and jam everything else I had to do into the afternoon and night. It all gets done if it has to be done, but if you try to get all the work out of the way first, you end up with no time left to write.

Though you never met your famous literary grandfather, do you feel the pressure of his masterful editorial hand on your shoulder?

I think I probably spent some time with him when I was a baby, because I lived in New York until I was two and a half. I have one memory of him being in the next room talking to an uncle of mine. I must have been about two. But his editorial presence has been very helpful to me. When I was working on The Simple Life, I knew I needed an editor. I sent the manuscript to lots of publishing companies, but I couldn’t find anyone willing to advise me. Then I thought that I could teach myself to edit myself. It ought to be possible for someone who was related to Max Perkins. And he always said that he never needed to edit Hemingway because Hemingway was good at editing himself. So I studied the book of Max’s letters, Editor to Author. I also read books about Max and his writers and while I was working on The Simple Life, my aunt, Bert Frothingham, and I put together a book of Max’s letters to his daughters. I believe Max taught me how to write and how to edit.

You really capture Vermont and its residents beautifully in Ordinary Magic, were your characters inspired by real people?

Everyone’s characters are inspired by real people to some extent. I think the difference is whether you take a person whole into your story, or whether you take certain portions of different people and put them together. That’s what I try to do. Sometimes I can find a photograph of a person I don’t know, and by looking at it long enough and hard enough, I feel as though I know the person. I found the photograph that became Cal in a junk store.

The book deals with a sensitive subject with the one of the main characters wrestling with an unplanned pregnancy and the possibility of abortion. Did you know how she was going to decide ahead of time?

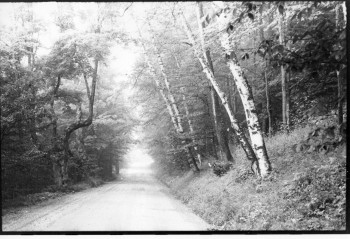

I think I could say that I hoped she would choose the way she did. It’s a funny combination of knowing and not knowing. I am always puzzled when people say they have no idea how their story will turn out, and yet of course, it becomes dead if you force it to go the way you meant in the beginning. I always think it’s like a road trip—you know something about the trip, roughly how long it’s going to take, where you are going to end up, maybe even what you hope to see along the way, but you don’t know what’s going to happen until you actually get on the road, and it can turn out to be very different than you thought it would be. For me, it has to be both at once.

Even though it is clearly in present day (abortion is legal) the story and its characters have a timeless quality. Is there a message in that?

I’m very glad if that’s true. I tried hard for it to be that way. I think it depends on what the story is about. If it’s about things that are important to people no matter when they live, then it can have a timeless quality, if you’re lucky.

Several of the main characters of the ensemble cast are men and you write them well. How did you get into the male mind in order to capture their voices?

My brother, who is an actor, told me something very important when I was working on The Simple Life. He said he never played himself. You have to be able to look at a person and make that person coherent, and you can’t do that about yourself, because you can’t see yourself. I was struggling with Isabel at the time. She turned out to be very hard, because I thought I could just write myself and so it would be easy. Since my brother said that, I think I have found it almost as easy to write men as to write women. I gave Cal lots of things that are important to me, for example. But he’s obviously a very different person also.

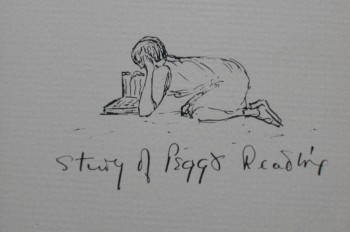

You include photographs at the beginning of each chapter. Can you share with us the story behind that concept?

I want a person reading my novel to feel that it’s an experience that person is having, so I want the novel to be very real. A photograph is a proof of that reality. I always wanted photographs in my novels, not ones of people because that might get in the way of how the reader pictured the characters, but scenes that would make the reality even more real. It’s one of the reasons I decided to publish my books myself. I might have been able to find a commercial publisher, but I knew I would never find one who would let me put in a lot of my own photographs.

What are you working on next?

I’ve started a new novel. This one is going to be about that strange and difficult country that is old age. I hope it’s going to be about death and sex also, but it’s just the beginning. Those are the subjects that I hope to write about anyway.

Tell us something that isn’t on the official bio.

I haven’t ever earned much money, but I’ve always been able to make good food. A year and a half ago, I started taking about fifty pounds of food to the food shelf every month. I raised extra food in the last two gardens, especially potatoes and carrots, things I can bring even in the winter. I bake extra nutritious bread every month too, and I almost always can get together a lot of eggs. My rule is that the food for the food shelf has to be the best, not the leftovers.

“The guys that wrote the best songs were the guys that wrote the most songs.” That was said by the daughter of a Tin Pan Alley songwriter. But it’s obvious, isn’t it? If you want to be good at writing, you need to do as much writing as you can. And there’s a corollary to that—you need to read as much as you can too. That’s the way to find out how other people have done it. Read the things you like best to learn how to write things you will like. And train yourself the way an athlete does. I spend time every day practicing being able to sit down, pick up my pencil and go, before the fear and doubt have a chance to make me timid. I also spend time writing without knowing what I’m going to say or where my story is going to go. I find that when I write that way, I stumble upon interesting ideas that I didn’t know I had, directions I couldn’t have planned for. But that’s what I do. What you should do is figure out what it is you want to write, what kind of writing you want to get good at, and then practice that a little every day until you train yourself. That seems much more useful than going to writing workshops where you write something and then have other people tear it apart. Quentin Tarantino said, “I didn’t go to film school. I went to films.”

“The guys that wrote the best songs were the guys that wrote the most songs.” That was said by the daughter of a Tin Pan Alley songwriter. But it’s obvious, isn’t it? If you want to be good at writing, you need to do as much writing as you can. And there’s a corollary to that—you need to read as much as you can too. That’s the way to find out how other people have done it. Read the things you like best to learn how to write things you will like. And train yourself the way an athlete does. I spend time every day practicing being able to sit down, pick up my pencil and go, before the fear and doubt have a chance to make me timid. I also spend time writing without knowing what I’m going to say or where my story is going to go. I find that when I write that way, I stumble upon interesting ideas that I didn’t know I had, directions I couldn’t have planned for. But that’s what I do. What you should do is figure out what it is you want to write, what kind of writing you want to get good at, and then practice that a little every day until you train yourself. That seems much more useful than going to writing workshops where you write something and then have other people tear it apart. Quentin Tarantino said, “I didn’t go to film school. I went to films.”

Would you like a free copy of one of my books? I want to get them in the hands of readers, so I have decided to send them to people who would like to read them. I haven’t decided how many to give away. I’ll decide that later.

Would you like a free copy of one of my books? I want to get them in the hands of readers, so I have decided to send them to people who would like to read them. I haven’t decided how many to give away. I’ll decide that later. an exclusive contract, so I had to stop selling books through Baker and Taylor and Amazon. That contract turned out to be a disaster, and I was left with most of the books I had printed the second time. Still, it looked as though I was getting close to breaking even.

an exclusive contract, so I had to stop selling books through Baker and Taylor and Amazon. That contract turned out to be a disaster, and I was left with most of the books I had printed the second time. Still, it looked as though I was getting close to breaking even. Send me an e-mail with your address, and I will send you whichever one you would like to read. If you read that one and want to read the other, send me another e-mail, and I’ll send you the other one. It’s as easy as that. If you are pleased or grateful, you can return the favor by putting a comment on my website about the book, and especially what you liked about it. Maybe your comments will inspire someone else to ask for a free book. You could give the book to someone who would like to read it. You could tell your friends to e-mail me and ask for their own copies of my books.

Send me an e-mail with your address, and I will send you whichever one you would like to read. If you read that one and want to read the other, send me another e-mail, and I’ll send you the other one. It’s as easy as that. If you are pleased or grateful, you can return the favor by putting a comment on my website about the book, and especially what you liked about it. Maybe your comments will inspire someone else to ask for a free book. You could give the book to someone who would like to read it. You could tell your friends to e-mail me and ask for their own copies of my books.